<English version below>

Los procesos heterocrónicos actúan sobre el tiempo y el ritmo de la transformación de la forma y tamaño de los individuos de una especie, en relación con los de otra especie, de manera que el desarrollo se amplía o recorta y su ritmo se ralentiza o acelera. Por ejemplo, los perros actuales son más pequeños que sus antepasados los lobos, tienen la cabeza más redonda, un morro corto en los subadultos y un comportamiento dócil.

Los bonobos (Pan paniscus) son muy diferentes a los chimpancés comunes (Pan troglodytes). Éstos son muy agresivos, capaces de matar a otros semejantes e incluso a crías, y se organizan en grupos con una jerarquía individual y sexual muy marcada. En cambio, los bonobos son más tolerantes, y en su grupo no tiene tanta importancia la jerarquía, pudiendo compartir con tranquilidad comida, crías y parejas. Pues bien, los bonobos presentan algunas partes de su cuerpo con proporciones de un chimpancé común subadulto.

¿Por qué sucede esto? Según la hipótesis de la autodomesticación, el proceso evolutivo ha favorecido la retención de rasgos juveniles y recortado el desarrollo de estructuras morfológicas que pueden estar asociadas a un comportamiento agresivo, sobre todo en la cara, como el tamaño de los colmillos o el abultamiento de la región supraorbital. Esto promovería el comportamiento colaborativo de grupo y la socialización (Bruner, E. La evolución del cerebro humano. EMSE EDAPP, 2018).

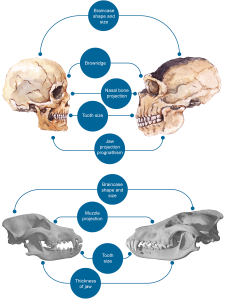

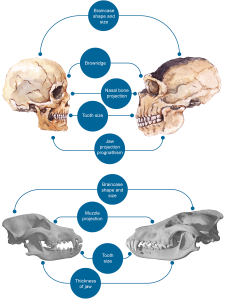

Salient craniofacial differences between AMH and Neanderthals (top) and between dogs and wolves (bottom). Credit: Theofanopoulou, C. et al. Self-domestication in Homo sapiens: insights from comparative genomics. PLOS ONE, 2017

Trasladar esto a Homo sapiens supone asociar a la autodomesticación rasgos exclusivos de nuestra especie, como el cráneo esférico, la cara corta, la pérdida del vello corporal o la explosión de la creatividad y la innovación tecnológica. Sin embargo, estos rasgos han evolucionado en mosaico: el cráneo esférico sí está muy asociado a la morfología sapiens desde hace unos 200.000 años, pero el acortamiento de la cara y otros rasgos se anticipan ya en especies como Homo ergaster y Homo antecessor hace un millón de años, la pérdida del vello corporal probablemente estaría vinculada con el desarrollo de un cuerpo completamente moderno en Homo ergaster, y la explosión creativa comienza hace entre 100.000 y 60.000 años.

Por otra parte, si nos detenemos en la cara, nuestra especie se caracteriza por la neotenia, es decir, la conservación de rasgos juveniles en adultos en comparación con la especie antepasada u otras emparentadas. La cara de un Homo sapiens adulto es sorprendentemente parecida a la de un Homo neanderthalensis infantil.

Se piensa que este proceso se ha acelerado desde el Neolítico. Existe una correlación entre el desarrollo de sociedades humanas de mayor tamaño y la pérdida de masa muscular y la reducción del tamaño corporal. El desarrollo social ha mantenido reducida la agresividad en nuestra especie, aunque muchos opinen distinto… Aunque tampoco podemos asociar esto a la explosión creativa y la curiosidad que nos empujó a colonizar el mundo, dado que éstas ocurrieron mucho antes. Tampoco podemos descartar que la reducción de nuestro cuerpo esté asociada a otro tipo de adaptaciones, como una respuesta evolutiva a la reconfiguración hormonal consecuencia de la transformación de la actividad física humana. En todo caso, varios estudios recientes apoyan la hipótesis de la autodomesticación:

- Los fósiles nos dan información, como la reducción de la capacidad craneal de los humanos modernos desde hace entre 10.000-20.000 años, como promedio un 10% en los hombres y un 17% en las mujeres (Henneberg, M. Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene, Human Biology, 1988). A este proceso podría también estar influyendo una reconfiguración cerebral para optimizar la elevada demanda energética de este órgano.

- Pero también la genómica nos aporta una información importante. Comparando los genomas de los humanos modernos con los de especies animales domesticadas, se ha observado entre ellos similares caracteres fenotípicos que están regulados por un mismo conjunto de genes, relacionados con la función cerebral, el comportamiento, la anatomía y la dieta, y que están asociados con aspectos de la domesticación tales como la docilidad o la gracilidad de rasgos fisionómicos. Y este solape genético es distinto respecto a lo observado en otros genomas humanos como los neandertales o los denisovanos. Es decir, presentamos caracteres fenotípicos gráciles y juveniles en comparación con los de los neandertales, igual que los de otras especies domésticas comparadas con sus tipos salvajes: perros con lobos, bueyes con bisontes (Theofanopoulou, C. et al. Self-domestication in Homo sapiens: insights from comparative genomics. PLOS ONE, 2017).

Una última hipótesis muy interesante para explorar, es la relación entre los primeros procesos de autodomesticación y los orígenes del lenguaje humano, planteada a partir de determinados comportamientos comunicativos observados en experimentos con perros y lobos, y otras especies animales (Thomas J. and Kirby S. Self domestication and the evolution of language. Biology & Philosophy, 2018).

Cráneos de Teshik-Tash (neandertal infantil de 7-9 años de edad) y humano moderno adulto. Crédito: Roberto Sáez

What is self-domestication?

Heterochronic processes act on the timing and rate of the transformation of the shape and size of individuals of one species, in relation to those of another species, in such a way that development expands or narrows and its rate slows or accelerates. For example, today’s dogs are smaller than their ancestors the wolves, have a more rounded head, a short snout in subadults and docile behavior.

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are very different from common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Chimps are very aggressive, they eventually kill others and even their offspring, and are organized in groups with a very marked individual and sexual hierarchy. On the other hand, bonobos are more tolerant, in their group the hierarchy is not so important, and they can share food, offspring and couples with others. It turns out that the body of the bonobos present some proportions corresponding to a subadult chimp.

Why does this happen? According to the self-domestication hypothesis, the evolutionary process has favored the retention of juvenile traits and cut the development of morphological structures potentially associated with an aggressive behavior, especially in the face, such as the size of the canine tooth or the supraorbital region. This would promote collaborative group behavior and socialization (Bruner, E. La evolución del cerebro humano. EMSE EDAPP, 2018).

Salient craniofacial differences between AMH and Neanderthals (top) and between dogs and wolves (bottom). Credit: Theofanopoulou, C. et al. Self-domestication in Homo sapiens: insights from comparative genomics. PLOS ONE, 2017

Applying this to Homo sapiens would involve to link with self-domestication some features unique to our species, such as the spherical skull, the short face, the loss of body hair or the explosion of creativity and technological innovation. However, these features have evolved in mosaic: the spherical skull has been closely associated with sapiens morphology for 200,000 years, but face shortening and other features are already anticipated in species such as Homo ergaster and Homo antecessor a million years ago, body hair loss is probably linked to the development of a completely modern body in Homo ergaster, and the creative explosion begins between 100,000 and 60,000 years ago.

On other hand, if we focus on the face, our species is characterized by neoteny, that is, the preservation of juvenile traits in adults compared to the ancestor or other related species. The face of an adult Homo sapiens is surprisingly similar to that of an infantile Homo neanderthalensis.

This process is thought to have accelerated since the Neolithic. There is a correlation between the development of larger human societies and the loss of muscle mass and the reduction of body size. The social development has reduced the aggressiveness in our species, although many can think different… However, we cannot associate this with the creative explosion and curiosity that led humans colonize the world, since that occurred much earlier. Nor can we rule out that the reduction of our body is linked to other types of adaptations, as an evolutionary response to the hormonal reconfiguration resulting from the transformation of human physical activity. In any case, several recent studies support the hypothesis of self-domestication:

- Fossils keep providing information, such as evidence of the cranial capacity reduction in modern humans since between 10,000-20,000 years ago, on average 10% in men and 17% in women (Henneberg, M. Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene, Human Biology, 1988). This process could also be influenced by a brain reconfiguration to optimize the high energy demand of this organ.

- But genomics also provides some important information. Comparing the genomes of modern humans with those of domesticated fauna species, similar phenotypic traits have been observed among them that are regulated by the same set of genes, which are related to brain functions, behavior, anatomy and diet, and that are associated with aspects of domestication such as docility or the gracility of physiognomic traits. And this genetic overlap is different from that observed in other human genomes such as Neandertals or Denisovans. This means that we present gracile and juvenile phenotypic characters in comparison with those of the Neandertals, as well as those of other domestic species compared with their wild types: dogs with wolves, oxen with bison (Theofanopoulou, C. et al. Self-domestication in Homo sapiens: insights from comparative genomics. PLOS ONE, 2017).

Finally, a very interesting hypothesis to explore is the relationship between early processes of self-domestication and the origins of human language, raised from certain communicative behaviors observed in experiments with dogs and wolves, and other animal species (Thomas J. and Kirby S. Self domestication and the evolution of language. Biology & Philosophy, 2018).

There is no real evidence that Neanderthals or Hominids other than Homo Sapiens lacked cresstivity or that Homo Sapiens because of physical differences somehow brought about a creative surge. Nor is there evidence that they did not have Cohesive Communities. Rather much has been lost, or destroyed through Geological Process such as Floods, Ice Ages etc… I maintain that the Art/Statues&Burials discovered show high degrees of Culture & Creativity.There are theories that many species of Hominids may have for a Period lived together & perhaps inter breeding together.At the very least there would have been knowledge & maybe even inter change such as Trade between them.

Me gustaMe gusta

Dear Surrealmothergoose,

Thefanopoulou and colleagues have provided a genomic evidence that supports other theories centered on self-domestication. These are collected and discussed here: https://www.academia.edu/37463867/Holocene_Crossroads_Managing_the_Risks_of_Cultural_Evolution

The role of paleoart is also discussed.

Me gustaMe gusta

Thank You for the reply.Having a Major in College both in Art & Anthropology I shall likely find this work fascinating.Glad to have access to other less Conventional Theories

Me gustaLe gusta a 1 persona

La autodomesticación se vería favorecida por la hibridación? Aceleraría su proceso?

Buenísimo el artículo, sugiero que hagas uno con la relación entre autodomesticación – hibridación.

Saludos.

Me gustaLe gusta a 2 personas

Ne Parle Espagnol. I am interested in this article .I can apply the methods discussed about Levelling & Copeing mechanisms to my studies of how Social Engineers prevent Cultural growth, sometimes even directing the course & direction of the Societies they target. Its a long article but worth reading

Me gustaLe gusta a 1 persona

Thank you for your interest. Indeed, the article could be helpful in such a project.

Me gustaMe gusta

Pingback: La autodomesticación del ser humano: | Filosofía en Villalba