Actualizado diciembre 2025

1) Koobi Fora, Okote Member y Chesowanja (Kenia): 1,5 Ma (millones de años)

En los años 80, en estos yacimientos se encontraron pequeñas áreas de tierra enrojecida asociadas a herramientas de 1,5 Ma (Okote) y 1,42 Ma (Chesowanja). Mediante técnicas de susceptibilidad magnética y luminiscencia se demostró que el coloramiento fue provocado por el fuego, pero se discute sobre si fue natural o provocado por la acción humana. El reestudio de los materiales de Okote en 2019 confirman la datación.

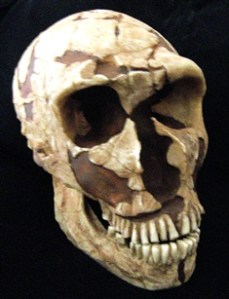

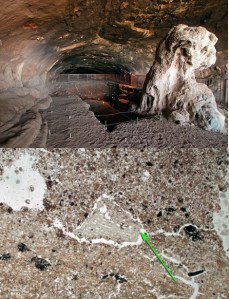

2) Cueva Wonderwerk (Sudáfrica): 1 Ma.

Se trata de una cueva donde se han encontrado evidencias de ocupación humana desde hace 2 millones de años hasta principios del siglo XX.

Unos restos de hogueras con cenizas y huesos (Berna et al., 2012), hallados por casualidad durante el estudio de los sedimentos donde habían aparecido unas herramientas líticas, se dataron en 1 Ma, anticipando en 200.000 años el anterior registro que se tenía de evidencias más antiguas de fuego controlado.

Estaban 30 metros adentro desde la entrada, haciendo improbable que fueran introducidos mediante causas naturales. Además se han encontrado en distintos niveles alrededor de 1 Ma. lo que sugiere que fue una zona donde se usó fuego en repetidas ocasiones.

Sigue leyendo